After graduating in composition at the Royal Academy of Music in London, English-born composer Gareth Coker traveled the world extensively to study music from different countries, including Japan, before completing the film scoring program at the University of Southern California. Coker's critically acclaimed soundtrack for Ori and the Blind Forest was honored with several prestigious awards, including the D.I.C.E. Award for Outstanding Music Composition. His success in the field led to him being awarded recognition as an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music (ARAM) for his significant contribution to the music profession. For his latest musical journey, Gareth Coker collaborated with Studio Wildcard on ARK: Survival Evolved, the open-world dinosaur survival-adventure game which recently launched worldwide for PlayStation 4, Xbox One and Steam PC.

You’ve worked on several game IPs now with ARK: Survival Evolved being released just last month. How have these experiences shaped you as a composer?

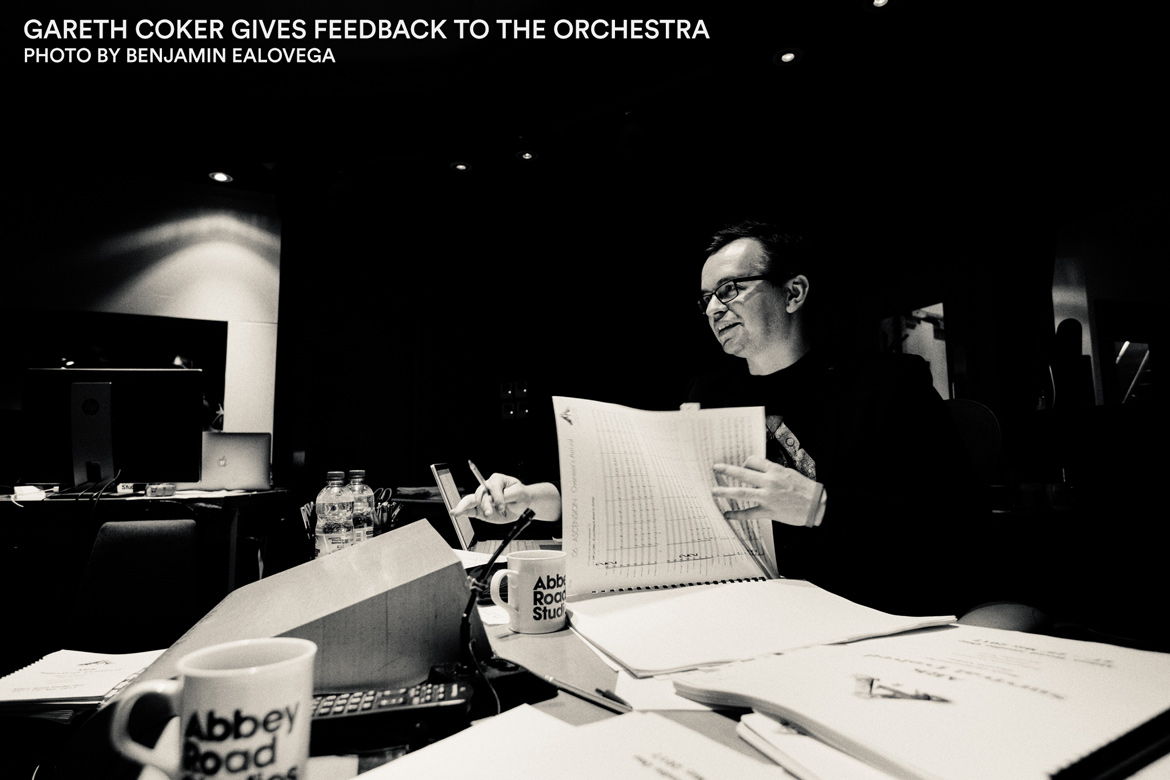

I have been very fortunate to have worked across a range of IPs that really allow me to exercise the creative side of my brain, as they have all been so different. ARK is about as different as it gets to Ori and the Blind Forest, which sonically is on the opposite end of the spectrum to The Unspoken, which in terms of intensity is also pretty much the opposite of the work I’ve done on Minecraft! I do like working on different projects because it keeps things fresh, and with each different style you’re always learning something new. One of the great things about music is that there’s always an opportunity to learn, and techniques picked up in one game soundtrack can easily be applied to the next one, whether the two games are related or not. Additionally, one can never have enough experience of working with the orchestra, whether it’s a chamber group of 22 musicians, or the behemoth that we had on ARK of 93 players, orchestration is a lifetime’s study!

Were there any elements to creating the soundtrack for ARK: Survival Evolved that were new or unfamiliar to you?

This is the first open-world multiplayer game I’ve scored. It’s also the first Early Access title I’ve scored. Both these factors present unique opportunities, and also unique issues. Being an open-world multiplayer game meant dealing with something of that scale for the first time. The island on ARK is enormous, and figuring out how to cover the island in terms of music was something that took a fair amount of time. The decision was made not to have ambient music and just use music to signify combat. The only real exception to this is the music that signifies time-of-day transitions (morning to midday, midday to night, night to morning). In the end, each biome in the game (jungle, mountain, grasslands, beach and more) has unique combat music, as well as the major bosses (Broodmother, Megapithecus, and the Dragon). The endgame is the only part of the game which is more scripted and controlled, otherwise, the score that plays is really defined by the player. I suppose it’s possible that some players might hear almost no music at all depending on their playstyle!

Regarding Early Access, the most unique phenomenon was dealing with the audience’s love for the version 0.1 music that would obviously be altered, adapted and moved around in the game in time for the actual release. The best example of this is with the initial early access release combat music. We had one track for daytime combat, and one track for combat at night. When we made the switch to having biome-specific music, it was quite a major and shocking change for the community as many of the earliest adopters had gotten used to the way combat music played in the game for well over a year and countless hours of playtime. In future, I’d definitely alter the way I handle putting in new music to early access games, starting from a broader base and increasing the number of updates just to smoothen out the process and perhaps reduce the potential of nostalgic attachment that can come with music.

Was it always a goal of yours to compose for games or was it something that happened to develop over time?

I don’t really have a preference between games, TV, film, commercials, at the end of the day it’s about getting the chance to tell a story. That said, I think I may have naturally gravitated towards games because I have been playing them since I was 4 and so I have a wealth of gaming experience to draw on when trying to create them. Obviously I’ve watched plenty of film and TV, but one has to start somewhere and games made the most sense for me.

Games are often taking advantage of the latest and greatest in technology. Have there been any advances in music technology that have impacted your creative process?

It’s easier than ever to get real musicians playing on scores, even if they are not in the same country as you. It’s possible now to have a plugin that enables the performer to basically ‘dial in’ to your music software and record multiple takes in realtime from around the world into the software. It essentially means you can book whoever you want as long as they are interested and budget allows. There are several examples of composers working with prominent YouTube performers and hiring guest artists. I think we’ll see a lot more of this in the coming years, and with the quality of musicians that there are across the planet, it’ll elevate game music just that little bit more.

On the technology and implementation side, I actually feel like the tools are ahead of the human mind. We have not been writing game music long enough to have unleashed the full potential of what interactive music can be, which to me is exciting because we’ve already come so far. Effective interactive music really requires an amazing synergy across departments, it cannot be made in a vacuum. Design, gameplay and audio teams have to work together to really nail the musical implementation. Unfortunately, while this kind of cross-department cooperation is possible on smaller projects, it is something that is tricky to scale up once projects become really big. However, it’s a matter of time before that’s figured out.

You are working on the sequel to Ori and the Blind Forest, Will of the Wisps. How does it feel to go back to an IP you’ve worked on previously and have a chance to create something new?

It’s both exciting and intimidating. One has to create something that is new, but also familiar. It is the first time I’ve done a sequel and there is obviously the expectation from the community to deal with. That said, we at Moon Studios have to block all that out and just concentrate on making Will of the Wisps the best game it can possibly be. I am looking forward to seeing how the team builds on the first game and also uses all the things we’ve learned over the years and how it gets applied to the new game. Finally, it was a major highlight to have been able to contribute to introducing the game on stage at E3 with the live piano performance. It’s great to have that kind of backing from Microsoft. It was also really fun to see all the reactions online and how excited people are for the new game, but of course, that’s where the expectation originates from too!

Are there any experiences or opportunities on the Composer Gareth Coker bucket list that you’d like to cross off someday?

There’s a long list of musicians I’d love to work with, and also a long list of studios that I’d love to record at, even after recording at Abbey Road! I’ve been incredibly lucky so far to have been given the recording opportunities I have, however, one always aspires to work with more. Working with musicians, whether it’s one or one hundred, can add real life to one’s work and I often find them a great source of inspiration because they make me want to write better material for them.

Do you have any advice for those aspiring to compose music for media someday?

It’s nothing particularly innovative in terms of advice, but you really do need to work incredibly hard and get your music out there. I think the most important thing is to finish work and not sit on it. If you’re looking for work, it’s a lot easier for someone to book you when you have completed projects under your belt. It is very hard to get something out the door, so if you are able to do it, the more confidence it will give potential clients to pick you. Additionally, I think self-awareness is incredibly important, knowing roughly where you are in terms of your technical skills, what you’re good at, and what you’re not good at. Write and compose to your strengths while working on your weaknesses. Aspiring composers definitely won’t be good at every skill required to be in the industry, so if, for example, you have a weakness in orchestration, find someone that is good at it and that can help you or at least teach you. If there’s one thing I’ve found about the game audio community over the years, it’s that the people in it are incredibly generous with their time and very willing to give, you just have to have the courage to ask.

Where can people follow you and/or your work online?

I’m pretty active on Twitter - @garethcoker and of course my personal website www.gareth-coker.net